Director: Michel Hazanavicius

Writer: Michel Hazanavicius

Year: 2011

Cast: Jean Dujardin, Bérénice Bejo, John Goodman

★★★★☆

To make a silent film that straightforwardly copies the style of the 1920s would be a gimmick. To put it simply, filmmaking has moved on. That is not to say that it has got better or worse – many silent films from that era are wonderful, but they are products of their time. Merely recreating an old-fashioned silent film in the modern age is impossible. It would seem hollow.

With The Artist, Michel Hazanavicius does not attempt to make a 1920s film, however much he borrows from them. Yes, it is shot in black and white in an old-fashioned ratio, the soundtrack is heavily reminiscent of the era, and there is no dialogue until the very end, but The Artist’s strength lies in the way it uses these aspects of the silent film, and transforms them into something else – something modern and self-reflexive.

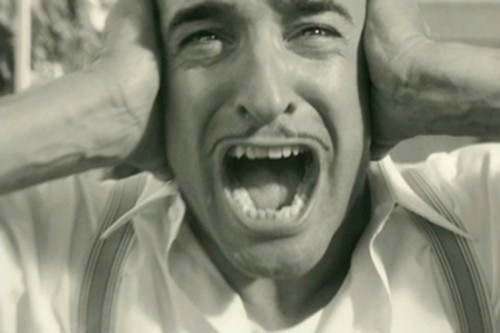

The sound of silence is all George Valentin can tolerate.

The film would not work otherwise. Its occasional breaks into irony are necessary, whether achieved by the use of sound or colour, or any other quirks of the style. The clearest example is during the star George Valentin’s (Jean Dujardin) nightmare, which sees him thrust into a threatening world of everyday sound. The strength of the silent world that Hazanavicius has created means that the rift caused by sound is unnerving, but the irony is that the film, like any other, is not set in a silent world at all. The scene works because we can empathise, yet to empathise in that scenario should be absurd.

Our sophisticated position as viewers from a distant future makes the on-screen action appear quaint, but this only deepens our connection with the characters. The Artist maintains a relationship between the audience and the screen that is rarely seen. In a crowded cinema, there were few who didn’t smile for the majority of the film, few who didn’t laugh out loud, and few who didn’t feel compelled to applaud at the end. If nothing else, The Artist is a charmer.

In part this is down to the story, which depicts a silent film star, Valentin, who falls in love with an upcoming actress, Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo), before his career is ruined by the arrival of the talkies. His character is not entirely sympathetic, showing from the beginning a clear ambivalence to his wife and eventually becoming extremely jealous in the wake of Peppy’s success, but the desire for him and the romance to succeed never deteriorates. Like any true silent film star, Dujardin is larger than life and infinitely expressive, which is where his charm lies. He is also permanently accompanied by his dog, Uggie, who more than once steals the show.

As it reaches its finale, the film becomes fairly dark. The black and white is used perfectly to deepen the mood and the music becomes increasingly melodramatic. Valentin’s downfall is touching and his perilous position is starkly contrasted to the dancing and frivolity that come before it. That is the beauty of making a film in this way – the contrasts – it forces distinction and doesn’t allow for subtlety, and if the film can bring the audience with it, as The Artist does, it makes for an enchanting experience.

There is nothing difficult or subjective about the film. It is designed to appeal to a wide audience, somewhat ironically given that many will dismiss it simply for the fact of its silence. It is very funny, and appeals to a sense of humour which everyone possesses to an extent, something most comedies are unable to do. However, it is not perfect. It is only gimmicky once, but unfortunately the gimmick comes at a crucial moment. It is a moment that has elsewhere been praised and will divide audiences, but one that is disingenuous and uses the medium in a way that manipulates the audience into thinking something has happened when it has not. Hazanavicius strikes a false note at the dramatic climax, and in a word the connection is broken. Bang! But only for a moment.